Of course you remember MaJoHa, the three martyred priests who… Scratch that. Just kidding.

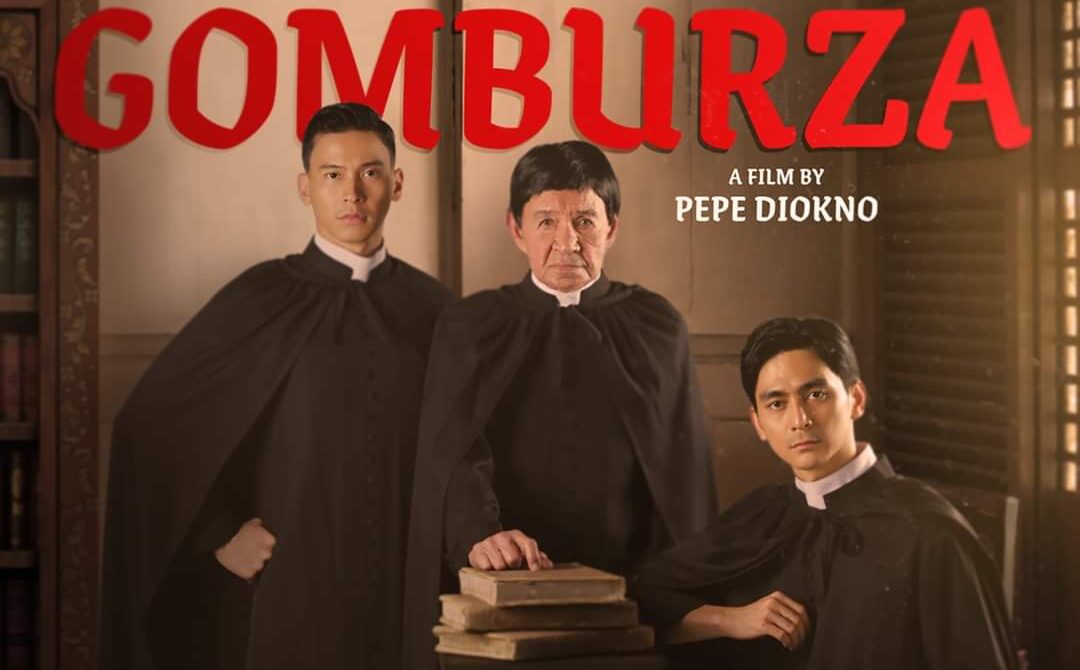

By now, people who have heard of how good Jose Lorenzo “Pepe” Diokno’s 2023 historical drama “GomBurZa” is have seen it in cinemas, so I guess it’s safe to talk about it without being an spoilery asshole.

Table of Contents

For the vaguely interested in history, I offer explanation for questions that ran inside your head when you watched the film. Although most of the film happened in the 1870s, knowing how the Filipinos reached that point at the start of the film requires going back to the 1540s when the Catholic Church held an ecumenical council in Italy, so that’s where we’ll start this discussion.

But first: If you haven’t seen the film, please know that there are heavy spoilers ahead. What am I saying? This is a historical film, so it’s not like you don’t already know how it ends for the titular characters Fathers Gomes, Burgos, and Zamora.

Obviously, I cannot give you in-depth lessons on history, so if you want to do a deep-dive, I have written words in bold letters to give you an idea about what else to read about.

1545 to 1563: The Council of Trent

You might have already heard of the Council of Trent in your high school history class. This was an important event in history that had important implications in how the film started. Of course there were so many reforms discussed during the series of meetings that lasted for 18 years, but let’s just focus on the ones that affected this story. Basically, during this council, it was decided that priests who were doing missionary work elsewhere had to share tasks with local priests.

Centuries later, in 1768, Charles III of Spain, apparently its most beloved monarch, advocated for secular priests to take over parishes in the Philippines. He took this policy from his father, Ferdinand VI, who initiated the secularization of the local churches. Ferdinand VI wanted to give the seculars the right to manage parishes, but the friars were against this because they believed that the indios were lazy and incapable of intelligent thought. Under Charles III, many indios were given he chance to study priesthood in University of Sto. Tomas and San Juan de Letran College. It is important to note that the archbishop then, Msgr. Basilio Sancho de Sta. Justa y Rufino, described the indios as even better than the Spaniards.

By 1768, some parishes held by the Jesuits, were given to the Recollects, whose parishes went to the seculares.

The film starts with Hermano Pule (Dylan Ray Talon), but the conflict really started way before him. The film did a great job explaining things to the viewers already. There were two sides that were at odds with each other. The regulares, or the friars, were the missionaries sent to the Philippine islands to convert locals. You know who they were, but the film only mentioned the Recollects, and there’s an explanation for this as well. I’ll explain why later. Be patient with me. We’ll do it slowly. Aside from the Recollects, the regulares were the Augustinians, the Dominicans, the Franciscans, and the Jesuits. These regulares (or “brothers”) are bound to their vows of celibacy, poverty, and their obedience to their Order. In the case of Jesuits, they vow to be obedient to—and remember this detail—the pope.

Meanwhile, the other side was the seculares. They were meant to do parish work. They were bound to their diocese. Archbishop Meliton Martinez (Jaime Fabregas), the archbishop of Manila, was a clear ally to the martyred priests. In almost all cases, the seculares were mestizos, or people with mixed descent. Father Mariano Gomes de los Angeles (Dante Rivero) and Father Jacinto Zamora y del Rosario (Enchong Dee) were known to be mestizos. I don’t recall anyone mentioning “mestizo” in the film, but this must be because I am writing this two days after I watched the film. Maybe I am misremembering. Secular priests were also creoles, or people born in the Philippines but with foreign parents. Jose Apolinario Burgos y Garcis (Cedrick Juan) was a creolo, and this was mentioned in the film. Secular priests can also be indios, a term derogatorily used by Spaniards to refer to native Filipinos.

1810 to 1821: Mexico Revolts

You heard it mentioned in the film that the revolution in Mexico was inspired by a priest. This priest was Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. By the time of the revolt, Charles III of Spain has been dead for more than two decades.

The idea that a priest would inspire a revolution was making the Spaniards anxious, of course. (Side note: Father Hidalgo was educated in a Jesuit institution, but in 1767, the Jesuits were also pushed out of Mexico because of, well, you already know what. Mexico and the Philippines had a lot in common when it comes to our histories.) Like Burgos, Hidalgo was a teacher and even became the rector of Colegio de San Nicolas Obispo, before he was expelled by authorities due to allegations of mishandling funds and changing the teaching methods at the school in 1792. He continued his parish work after that. Later on, Spain would be invaded by Napoleon Bonaparte.

In 1811, Father Miguel Hidalgo led men into a revolt against the Spanish regime. After his capture and execution, one of his former students, Father Jose Maria Morelos, became the new leader. He would eventually be captured and executed as well.

The difference between Hidalgo and Morelos, and the GomBurZa priests was that the two Mexican priests took arms while the Filipino priests, although active members of the secularization movement in the country, were not in any way connected to the armed struggle then. All five priests, however, had significant effects to the independence movements in both colonies.

1815: The End of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade

Just before Mexico gained its independence from Spain, the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade ended. Trades to, from, and via the Philippines did not have to go through Mexico. Boats (by the early 19th Century, there were already faster steamboats) directly carried books and other reading materials to the islands, effectively sharing liberal ideas to the educated masses. Filipinos, or the natives of the different Philippine islands (Remember that they don’t call themselves Filipinos yet. Right, Sebio?), were becoming more and more familiar with liberalism, which you hear a lot in the film. While conservatives were afraid of changes, liberals welcomed them. The friars were conservatives afraid of the possibility of inculcating to the masses ideas of self-determination. If you want to know more about liberalism in Europe during this period, this is your best source.

Apolinario de la Cruz or Hermano Pule was born a year before the end of the galleon trade. The film opens with his story as told by Father Pedro Palaez y Sebastian (Piolo Pascual), also a known liberal and leader of the secularization movement.

1868: La Gloriosa

In the mid-19th Century, Spain was facing a lot of turmoil. The Glorious Revolution of 1868, also called La Gloriosa or La Septembrina, ended with the fall of the monarchy. Spanish liberals and republicans overthrew the monarchy led by Queen Isabelle II (if I am not mistaken, the great, great, great grand-daughter of Charles III of Spain). They were successful in the overthrowing of the monarchy, all right, but were they effective in the aftermath? Not really.

While there was no monarchy, the Spanish legislators (called the “Cortes,” which you would hear a lot about in your history classes) instituted a Spanish constitution, but they also voted against making Spain a republic. For a while, Francisco Serrano y Dominguez was the king regent while the Cortes was having difficulties agreeing on who to elect as a king.

After the fall of the monarchy, Carlos Maria de la Torre y Nava Cerrada (Marco Lobregat) became the governor-general of the Philippines. Governor-generals were basically the heads of state of the Philippines, but they were ruling on behalf of the Spanish monarchy. De la Torre was well-loved by the native Filipinos, you saw that in the film as well. He removed media censorship, he befriended secular priests including Burgos (since he was the parish priest of the most important church in the Philippine Islands), and made other liberal reforms.

1870: Amadeo I

In 1870, the Spanish Cortes elected the Italian prince Amedeo Ferdinando Maria di Savoia as its new king—Amadeo I. The monarchy is back. As an effect, the liberal policies by de la Torre would only last until April 4, 1871, when he was replaced by Rafael de Izquierdo y Gutiérrez (Borja Saenz de Miere), who used the friars’ anger towards the secular priests.

You see, at the start of the film, the secular priests and the Recollects were having a rift due to the management of the parishes. When the Jesuits came back to the Philippines in the 1860s, they had to get their parishes back—the same parishes that went to the Recollects when they left. The secular priests wouldn’t let go of the parishes held by the Recollects almost a century prior, thus, the start of the film.

The new governor-general seem to have used this at his advantage when the Cavite Mutiny happened in 1872.

1872: Cavite Mutiny

Notice the language we’re using when calling this uprising led by Sgt. Fernando La Madrid. It’s a mutiny. Not a revolution. A mutiny is an uprising held by soldiers to overthrow someone in power, while a revolt is when civilians are involved. Up to this day, we call this a mutiny. Memorials in Cavite call it mutiny. No one calls it a revolt, and yet the fathers Gomes, Burgos, and Zamora were arrested, implicated, accused as the masterminds, and were executed for it.

Filipino soldiers were growing more and more discontent with the new governor-general. They were taxed unlike the Spanish soldiers and forced labor was reinstated.

The film says that it is based on the research by Rev. John N. Schumacher, SJ (1927–2014). What he found was that the mutiny was part of a larger conspiracy to overthrow the Spanish government and that the funds for this conspiracy came from liberal Filipinos Maximo Inocencio, Crisanto de los Reyes, Enrique Paraiso. After the trials, you see them only exiled to Guam. Francisco Zaldua blamed Burgos instead. Other historians theorize that Izqueirdo was a mason, and therefore spared the masons Inocencio, de los Reyes, and Paraiso from the garrote.

In reality, the soldiers who joined the Cavite Mutiny were used as pawns by the rich and powerful. Oh, Philippines. You never really changed, did you?

Gomes, Burgos, Zamora

Mariano Gomes was a mestizo from Sta. Cruz, Manila, but he was the parish priest of Bacoor, Cavite for a long time before the Cavite Mutiny and his execution. He was the oldest of the three priests and was loved by the locals because he lent them money, built them infrastructures, and served as an effective negotiator between the authorities and insurgents.

Jacinto Zamora was from Pandacan, Manila, and was the parish priest of Marikina. Like Gomes, he had unknown ethnicity, but they were both known to be mestizos. He was only slightly younger than Burgos.

Jose Burgos, who was a full-blooded Spaniard born in the Philippines, was from Vigan, Provincia de Ilocos. At the time of his execution, he had seven degrees including two doctorates. He was the parish priest of the Manila Cathedral. Like in the film, he was one of the teachers of Jose Rizal’s older brother Paciano.

Sebio the Tagalog

In the film, you see the use of the word “Filipino” become central to the conversations. At the time, no one was really using the word Filipino the way we would use it today. People will only refer to someone as Filipino if, like Burgos, they had foreign parents and they were born in the Philippine islands.

So when Sebio, the server boy, was asked what he was, he answer, “I am a Tagalog,” that was symbolic of the way most natives viewed themselves. In a way, that was helpful to the Spanish rulers. The natives did not see themselves as the same people who had similar roots, similar experiences, similar aspirations—so naturally, a widespread revolution will never come to fruition. That was true until Jose Rizal dedicated El Filibusterismo, his second book, to the three martyred priests.

Sidenote: The name Sebio kinda rings a bell, doesn’t it? I have a theory that Director Pepe Diokno chose that name in honor of Eusebio Roque, also known as “Maestrong Sebio,” who led the Kakarong de Sili Battle of 1897.

Who was the Long-Haired Indio?

The Spaniards used the word “indio” derogatorily, but Filipino would later use, reclaim it, and embrace the term. In a way, the evolution of that word was shown through the long-haired server who was listening to them while they talk about the secular priests and the natives.

It’s hard to miss the guy because he was always present. Here he is in a screenshot of the trailer. No one really knows who he is, but we can’t be wrong in thinking that he is the representation of all the indios—first a server who dislikes the friars, then someone who understood the friars and how they were used by Izquierdo; then a revolutionary who told the stories of the martyred priests to other fellow revolutionaries.

That’s it. I hope you learned a thing or two from reading this long post. Like I said, you can do your personal deep-dive if you read more on the texts in bold letters. Let me know if you have questions via ra@ravstheworld.com so I can answer them if I can. For now, please share this post to your friends. 🙂