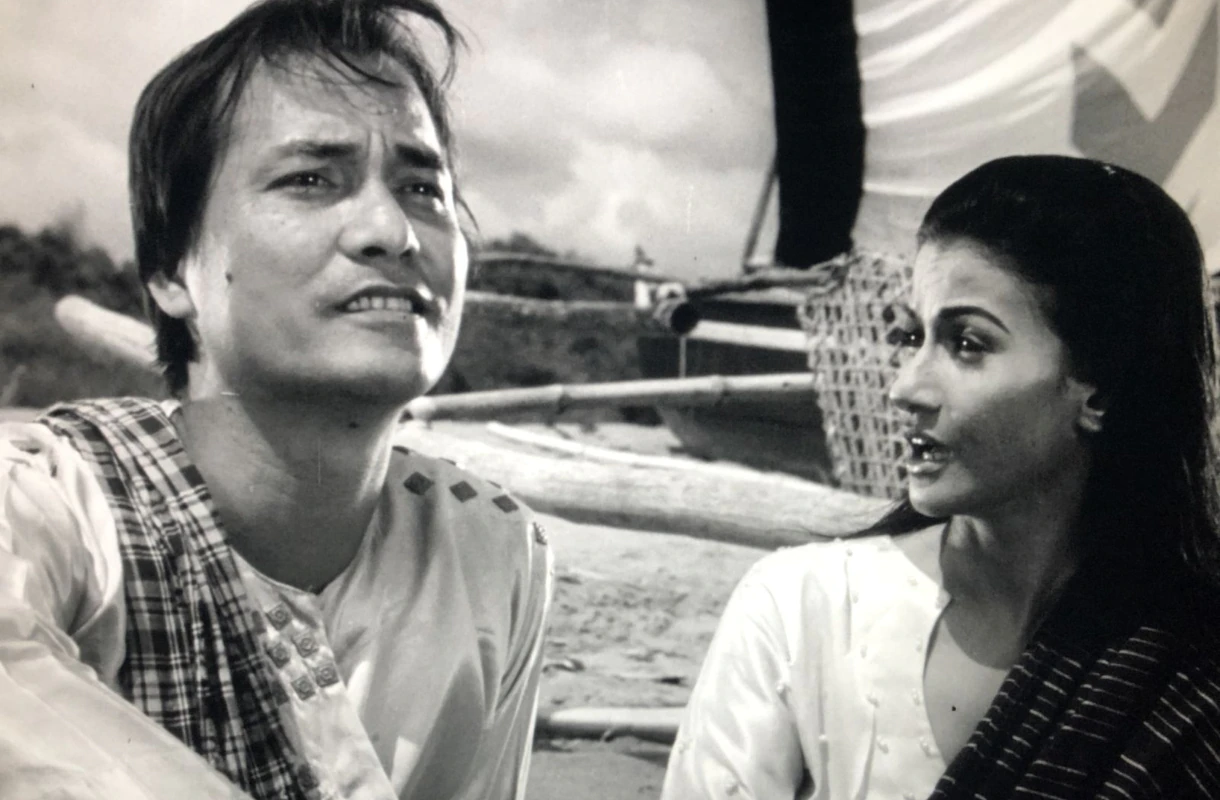

The 1957 film “Badjao: The Sea Gypsies,” a classic from the now defunct LVN Pictures, was restored in 2020. ABS-CBN Film Restoration screened the multi-awarded film for free on Tuesday, allowing today’s generation to see the film that stars Filipino cinema legends Rosa Rosal as the Tausug royalty Bala Amai, Tony Santos Sr. as the Badjao protagonist Hassan, and Jose de Cordova as Tausug leader Datu Tahil.

Other cast members include Leroy Salvador as Asid, Vic Silayan as Jikiri, Oscar Keesee as Ismail, and Pedro Faustino as the Badjao leader.

In 1957, director Lamberto V. Avellana won best director at the Asian Film Festival, Rolf Bayer won for his screenplay, Mike Accion won for the cinematography, and Gregorio Carballo won for his editing. Regardless of these awards, the film is relevant now more than ever due to the humanitarian crisis in Gaza Strip. The film is a lesson on diplomacy amid conflicts concerning territories. It does not shy away from criticizing capitalism as the root cause of all conflicts. But as a product of its time, the film has a problem when it comes to gender, something that we must also address if we want a thorough discussion of the film’s impact on contemporary viewpoints.

Table of Contents

Diplomacy

“Badjao” is a story of two peoples—the Badjaos are sea-dwelling men and women, who are proficient in looking for azure pearls, while the Tausugs are land-dwellers who look down on them. “Looking down” is an understatement because some of the Tausugs are oppressive towards the Badjaos. Silayan’s Jikiri, for example, would feel no remorse burning down a Badjao’s boat if he does not get what he wants from them.

Datu Tahil, the Tausug chieftain, respects the Badjaos’ forthrightness and bravery. He soon allows them to fish in the waters near their territory’s coast when the Badjao leader demands—no, request—that they be left alone. It was also implied that Datu Tahil respected Hassan, the protagonist, for not ratting out on Jikiri, even though he almost lost his boat.

“We don’t wish to harm anyone,” Hassan tells Datu Tahil after he promises that he will punish whoever wronged them. This is basically Hassan refusing to tell the datu that his right-hand man was the culprit. “Out only aim is to be left peacefully in the vastness of the ocean, our home,” he said, to which the datu gave a positive response. This diplomacy from the Badjao leader and Hassan earned them the respect from the datu.

While negotiating peace among the territories, Hassan sees Datu Tahil’s niece Bala Amai, who later becomes his trusted wife but not before he leaves behind his Badjao ways to the displeasure of his family.

When Hassan and Bala Amai married, it seemed all his worries were over. Before their marriage, he had already defeated in battle his arch-nemesis Jikiri—who wasn’t just Datu Tahil’s right-hand man but also an effective disinformation agent ready to make up lies about the Badjaos. So no Jikiri, no problem, right? Nope. There’s Ismail, but we shall get to that later.

Human rights

The themes of human rights are all over this film. There’s discrimination and prejudice towards the Badjaos, who are constantly struggling for freedom.

When one night Bala Amai fails to return home after trying to warn the Badjaos about the ill intentions of some Tausugs, the land-dwellers were quick to blame sea-dwellers. A battle was only avoided when Bala Amai was quick enough to explain to her uncle what really happened.

In the first half of the film, the Badjaos are lucky enough to have negotiated with a Datu Tahil that’s free from corruption. In the second half of the film, that changes.

Capitalism

The trader Ismail has been offering Datu Tahil a huge amount of money for the pearls from the Badjaos.

Here is when the story shows the main antagonist of the story. It’s not the Jikiri. He’s long dead. It’s not the Tausugs who are prejudiced against the Badjaos, although their hatred definitely factor in. It’s the exploitative nature of Ismail’s visits to the Tausugs, offering them riches, so that the latter would impose suggestions on the Badjaos for selfies reasons.

Blinded by the possible riches, Datu Tahil asks Hassan to dive for pearls for him, but the former Badjao refuses. Datu Tahil’s men then burns Hassan’s hut, endangering the life of his wife.

However, while this film gives us a lesson on how diplomacy could be done by meeting eye-to-eye and by criticizing human rights abuses and capitalism, this film has within it a problematic way reflecting gender norms. It does not criticize how Bala Amai is viewed by the men around him, including by the protagonist Hassan. This weakness in the film’s narrative is surely a product of its time, so we can forgive it for that.

Gender

Bala Amai, throughout the film, has been treated as an object. Her would-be husband Hassan has always viewed her as someone to be owned. Datu Tahil sees her as someone to be given away for something in return.

Bala Amai does not question this, nor does anyone around her. The story fails to give her a period to reflect on how she is treated.

After the wedding, I thought for a second that she would start a long-ass speech about being owned for her sexuality when she started running away from Hassan. But alas, she does not.

But the film does attempt to show her as a strong, independent woman. She stops a battle. She warns a community about an impending danger from a community to which she belongs. Aside from that, there’s no other layer given to her. She wakes up from a nightmare about Hassan leaving her for the sea. This scene tells us she is weak without him, that her whole being is not defined by being his wife. When Hassan delivers his long and rousing speech about his humanity, she was there in the corner weeping.

Bala Amai was just used to give Hassan an even more macho image. You, the viewer, have to root for the Hassan and Hassan alone. When you root for Bala Amai, who is also a victim of the Tausugs’ human rights abuses, the film fails you.

Let’s imagine a “Badjao” remake. What if despite his attempts to become a Tausug, forget his Badjao ways, and be a land-dweller, Hassan fails to convince Bala Amai to marry him because she loves someone else? Another lady, perhaps, from a different tribe? A new Bala Amai would end up as the new female datu, a dayang-dayang, if you will. As the leader, she shuns the capitalist out of their community, imprisons the former datu Tahil for attempting to murder her former lover, and she becomes the hero of both the Tausugs and Badjaos.

That version would inspire more women to question their place in society and then be sure of it.