You’ve seen them written in all capital letters. Though sometimes they do tell us where the story took place, it is not always the case. Let me explain.

Hi! This is Journo Bites, a series of quick journalism tips from yours truly, so that bit by bit, you understand why journalists write and report their stories the way they do. Before I continue my explanation about why journalists write places in capital letters before the lead paragraph, please like RA vs the World on Facebook and visit this page to ask me any question about journalism that has been bugging you.

Now back to that topic.

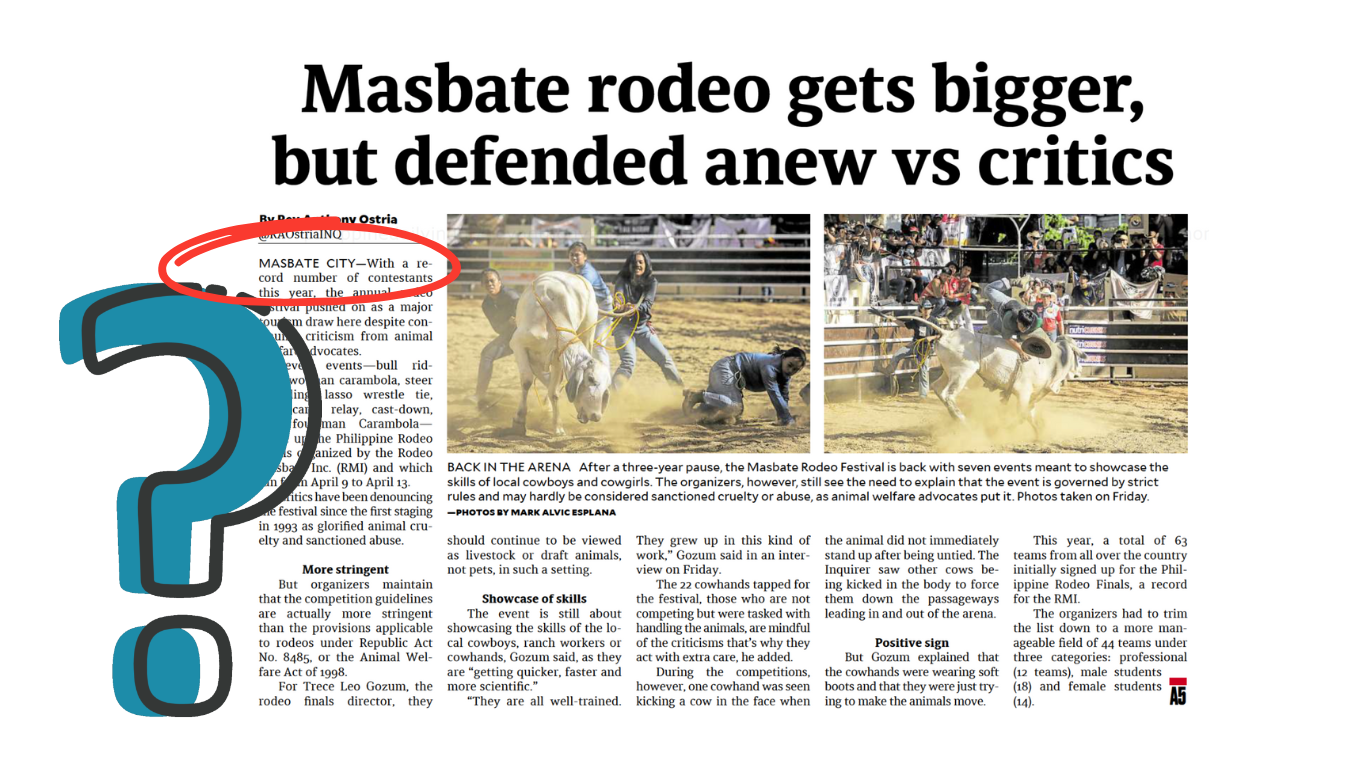

The bit before the lead paragraph (the first word, sentence, or paragraph of a news story) is called a dateline. This indicates where the journalist was when he or she was reporting on the story. (By the way, there’s a difference between reporting and researching, but that’s a topic for another day.)

This means that the dateline may not exactly be the place where the story took place. For example, when a reporter is in Quezon City, but the incident happened in Lucena City and the reporter called his or her sources to ask for information and comments, the dateline should be QUEZON CITY, followed by an em dash.

Datelines are usually written this way:

- If it is a city, we only write the city. The name province of the province is not written. The city name is written in all capital letters. For example,

- LEGAZPI CITY—And then the lead here…

- NAGA CITY—And then the lead here…

- CITY OF CALAMBA—And then the lead here…

- If the dateline is a town, we write the name of the town in all capital letters, and the first letter of the province in capital letter. For example,

- PILI, Camarines Sur—And then the lead here…

- GUINOBATAN, Albay—And then the lead here…

- The Associated Press Stylebook states that datelines may not be limited to towns and cities. In the United States, “Census-designated places, townships, parks, counties, or datelines such as ‘ABOARD AIR FORCE ONE or ON THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER” can be used, according to the AP. I am not familiar with census-designated places or townships in the Philippines (we define this term differently that the US), so let’s skip that. We don’t have counties. RIZAL PARK can be used as a dateline. ON THE PASIG RIVER or ON THE BICOL RIVER can be used as datelines. If a reporter is on Kalayaan One or any plane en route to anywhere while reporting on the story, ABOARD KALAYAAN ONE can be used as a dateline. In this story, the dateline “ABOARD THE BRP GABRIELA SILANG” is used.

When you see these datelines written, you will not see the reporter write name of the place in the lead paragraph anymore. If the dateline is LEGAZPI CITY and the reporter needs to mentioned the “where” of the story in the lead paragraph, or anywhere in the story, he or she will usually write “in this city.”

But what about if the journalist went to multiple places when reporting on the story? We do this a lot in our reporting. Sometimes you interview your sources in one city, then 30 minutes later, you’re in a different city writing your story. In cases like this, the reporter must write where the story occurred as his or her dateline. But some stories occur in multiple places at the same time. During typhoon coverage, for example, while it’s more strategic to be in Legazpi City where you’re closer to most of your sources, it is still better to go to other towns and cities to see what the situation on the ground is.

Let’s say the reporter was in Legazpi City to interview meteorologists or local officials. A few minutes later, he or she is in Daraga town to check on the situation in evacuation centers. Then half an hour later, he or she is in Guinobatan town to interview another set of sources. In this case, the reporter has these choices: It’s perfectly accepted for the story not to have a dateline and the journalist just makes it clear in the story where each interview took place, or he or she can use the place where the story was filed as the dateline, or—and this is what I do—choose the place where the most significant event or the angle took place.

And how about stories written by multiple reporters who are in separate areas? This happens a lot as well, especially for us in the bureaus. Our stories often are collated with other similar reports from different parts of the country. Whose dateline shall the editor use? Obviously there can only be one dateline, so the editor can make that decision. At the end of the story, there should be a note in the end explaining where each reporter was. This can be done in what is called a tagline. In the Philippines, however, it is not a common practice to write such a note. (I’ll write about the difference of a byline from a tagline in one of my Journo Bites posts someday.)

As journalists, we work hard to compile datelines, each one a significant indicator of the development of the stories we write. It’s similar to posting a place on social media with the responsibility of sharing the history of a town. Out of all of mine, the dateline from the inaugural Youth Climate Summit in New York is very dear to me. My actual goal, though, is to chronicle each town and city in Bicol, one by one (baka may story suggestions kayo diyan from your hometown). When it’s all covered, I might even reach for a dateline from Mars one day.

Thank you very much and please share this post. You can use the buttons below to share this explanation.